Electric Hummer Means ‘Watt Guzzlers’ Are Here. That’s A Good Thing

Well, that didn’t take long. As EVs have evolved from curiosities to common sightings, we’ve finally found a way to make them absurd.

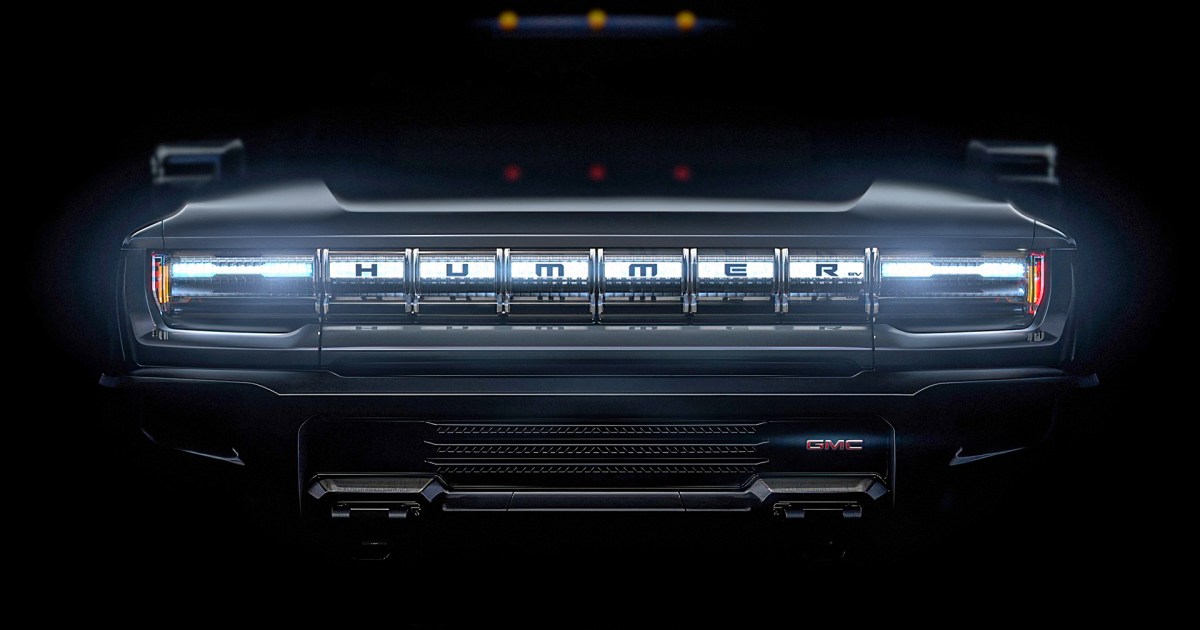

First, Rivian trotted out the modest R1T, a reasonable replacement for midsize trucks like the Toyota Tacoma. Then Elon Musk upped the stakes with the pavement-stomping, cone-crushing Tesla Cybertruck. And now GM has turned the macho posturing to 11 with the GMC Hummer, a rebirth of the military-inspired icon that Arnold loved, and environmentalists loved to hate.

1,000 horsepower. 11,500 pound-feet of torque. Zero to 60 in under 3 seconds. Except it’s electric now, you see? So we can all stop worrying about being so wasteful.

Sort of. Most people assume that EVs are environmentally friendly by default. However, we’re approaching the point where EV technology stops being used for efficiency, starts being used for excess. We’re entering the age of the watt guzzler.

That will make early EV adopters cringe, but don’t worry. It’s a good thing.

Most people aren’t buying EVs, yet

That’s because EV adoption is abysmal right now, and watt guzzlers — imperfect as they are — could help fix that. In 2018, EVs represented just 1.96 percent of all the vehicles sold in the United States.

Sales are concentrated in coastal states like California, Washington, and Oregon, while the South and Midwest collectively laugh off the segment. In North Dakota, just 95 people bought EVs in 2018, or 0.24 percent of all cars sold there that year. Wyoming sold a whopping 92.

These are the same states where pickups and SUVs rule. Ranchers may not love the look of the Cybertruck, but they love the segment. The map of states where the F-150 rules, and the states with the lowest EV adoption, could be one and the same.

Porsche Taycan Ronan Glon

Porsche Taycan Ronan Glon

We don’t have efficiency figures for electric trucks yet, but look at another performance-first EV: the Porsche Taycan. It goes 0 to 60 in 2.4 seconds, making it faster than the Tesla Model S, and the third-quickest car Car & Driver has ever tested, after the Porsche 918 Spyder and Lamborghini Huracán Performante. It weighs an outrageous 5,132 pounds ,and in terms of efficiency, lands at the very bottom of the EPA’s list of new electric cars. The range-topping Tesla Model 3 wrings double the miles out of equivalent electricity.

To the green crowd that has championed electric vehicles for the past decade, cars like the Porsche Taycan and GMC Hummer miss the point. Yet they’re accomplishing something else. The rest of the country is finally starting to notice EVs. Going green used to be the main selling point, but as watt guzzlers arrive, the other benefits of electricity are getting their time to shine.

Rivian R1T Image used with permission by copyright holder

Rivian R1T Image used with permission by copyright holder

The outrageous torque of electric motors makes setting 0-to-60 records almost unfair. The Rivian can perform a zero-radius tank turn, and instead of an engine, it has a front trunk (“frunk”) big enough for your cooler. The Cybertruck will dip its bed to load your quads, which are electric and charge in the back, naturally. And with bidirectional chargers, these vehicles can power your house for days when the power goes out.

You don’t need to be a kombucha-chugging urban kale farmer to appreciate these benefits. You might hate the Prius, yet find some love for an electric Hummer. That’s a good thing. It means the EV field is growing. In 2019, only 11 percent of American buyers opted for a compact car — the segment favored by drivers seeking efficiency above all else. That means 89 percent of buyers have priorities that lie elsewhere, from cargo capacity, to towing, to comfort. Converting any of those buyers to an EV is a net positive, even if they’re choosing watt guzzlers over the Model 3.

The math behind watt guzzlers

Consider the case of a would-be F-150 buyer. The most efficient version of it, with a 2.7L turbocharged V6, emits 402 grams of CO2 per mile, according to the EPA. Can the extremely inefficient Porsche Taycan really be better?

The EPA doesn’t offer CO2 estimates for electric vehicles, because they vary based on how that power is generated. To estimate, I used the EPA’s 2018 national average of .94 pounds (429 grams) of CO2 for every killowatt-hour generated. Based on the Taycan’s 68 MPGe rating, it can travel about 2 miles for every killowatt-hour of electricity consumed. The math says it generates only 214 grams of CO2 to travel a mile, barely more than half what the F-150 emits.

Ford F-150 Raptor Image used with permission by copyright holder

Ford F-150 Raptor Image used with permission by copyright holder

Even if we assume a worst-case scenario and charge our Taycan in the coal-heavy Midwest, where electricity comes at a cost of 1.66 pounds of CO2 per killowatt-hour, it still consumes 376 grams per mile. In the hydro-happy Northwest, it would consume just 144 grams per mile.

Would it be better if everyone opted for a Model 3? Sure. But environmentalists shouldn’t let perfect be the enemy of good.

Welcome to the EV party, Hummer fans. There’s a cold Bud in the frunk for ya.