HazAdapt’s Ginny Katz on Making Emergency Response Inclusive

Image used with permission by copyright holder

Image used with permission by copyright holder

In the grip of an emergency, the first move for many Americans is to call 911. The emergency response system has been around for decades, but like many institutions, it has struggled to keep up with technology. Call centers are easily overwhelmed in big emergencies, they often can’t track the locations of people calling from cell phones, and they’re vulnerable to hacking. An egregious example of this came in 2017, when a hacker used a malicious link on Twitter to hijack thousands of phones, forcing them to call 911 repeatedly, flooding call centers with false alarms.

“I’ve been studying and working in disasters, diseases, and emergency management for over 10 years,” says Ginny Katz, founder and CEO of HazAdapt. “At the end of my master’s degree, I really began to dive into the tech because I thought we really need some better technology here, and it just seems like what’s on the market today is not cutting it.”

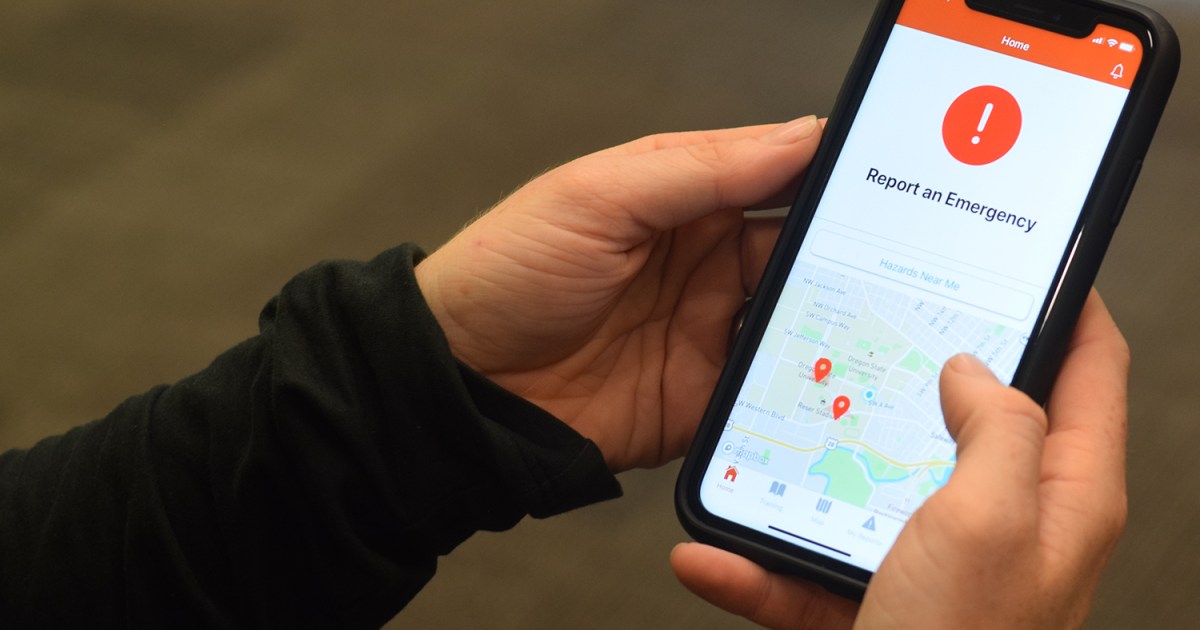

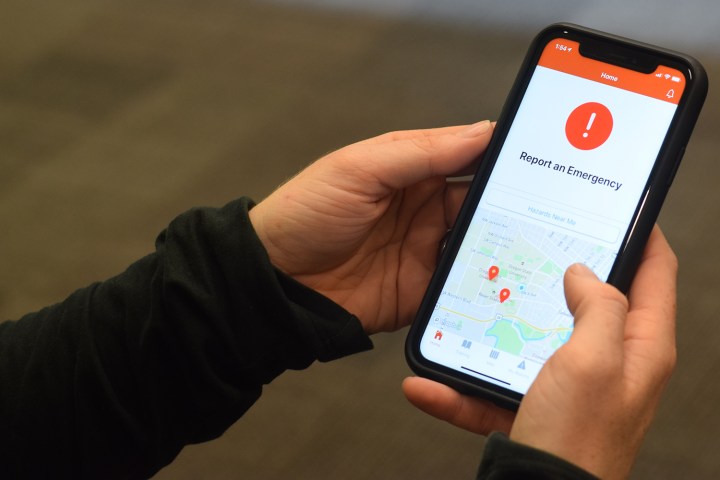

HazAdapt is developing an app that aims to provide users critical information in emergencies, but also allow them to better communicate with public safety officials and each other.

From a fire, a spark of inspiration

The idea of creating an emergency response app came after Katz had her own brush with danger.

Ginny Katz, founder of HazAdapt Image used with permission by copyright holder

Ginny Katz, founder of HazAdapt Image used with permission by copyright holder

“There was actually an emergency here on campus. It was an older building, so it didn’t have automatic alarms, and didn’t even have sirens that would automatically happen or sprinklers,” she says. “So a fire started, and one thing led to another, evacuation didn’t happen. It became … not too late, but the fire department wasn’t called as efficiently as needed. And people were walking in and out of the building, myself included, without knowing it was burning. And so people got exposed to chemicals, and there’s nothing really out there that would have prevented that.”

“So I was thinking to myself, I can walk near a Starbucks and my Facebook would say ‘Hey, do you want to write a review for Starbucks?’ but I don’t know where emergencies are based on my location. That’s a problem.”

Smartphones are ubiquitous, and as Katz points out, companies like Facebook use them all the time to blast users with requests and updates (no, Google Maps, I’m not going to review restaurants for you, you’re a billion-dollar company and can hire someone to do it!), so it’s refreshing to see an app proposing to save your life rather than just trying to squeeze money or data out of you.

How does HazAdapt propose to do it?

Inclusive design

As Katz explains it, HazAdapt’s goal is to close “really deadly communication gaps that happen right now in the current 911 system and mass notification system.” Antiquated telephone lines can be one form of deadly gap, but there are others; even the emergency alerts that public safety officials send via text message are lacking.

“Those messages often simply warn you something is happening,” Katz says, “but they really don’t tell you what you can do to survive, to overcome, and that information is almost absolutely never personal, it’s just generalized for the public. And that’s a big concern because disasters don’t discriminate.”

Everyone with a cell phone might get the same government text in an emergency, but not everybody has the same needs in those situations.

“For instance, someone who is wheelchair-using is going to need different evacuation instructions than someone who isn’t,” Katz says, “or someone who is visually impaired, they need that alert in a way that’s not text-based.”

Android 10 emergency icon. Julian Chokkattu/Digital Trends

Android 10 emergency icon. Julian Chokkattu/Digital Trends

HazAdapt is shooting for inclusivity, which Katz calls a “vague term because there are so many different facets of a human.”

Aside from the many forms of identity we might typically think about — gender, race, religion, political affiliation — a person can have any number of traits that might factor into an emergency. Do they have a physical impairment? Do they live alone? Have any kids? Do they live near any neighbors or hospitals? Can they drive or not?

By tailoring an alert to a specific user’s needs, HazAdapt aims to make sure everyone gets the information they need in a crisis. It also wants to make it easy for users to send information as well.

“Normally, we all call 911 when there’s an emergency,” she says, “but 911 quickly becomes overwhelmed because we’re still relying on dated technology. So HazAdapt makes it much easier for us as civilians to send an alert to the appropriate authorities. Not only can you send an alert that’s specific to that hazard, but you can also send the relevant information about you.”

A particular trait that HazAdapt is really keen to accommodate is problem-solving style.

“Someone who is very tech-savvy is going to use an app differently from someone who isn’t very tech-savvy,” Katz explains. “So when we’re designing inclusively, we need to make sure we’re designing a UI that caters to both of those needs.”

In the quest for an app that suits all users, Katz says the team uses an “inclusive scrum” method of software development, adopting the persona of people who are not “technology savvy” and going through the process of using the interface and imagining if it would make sense for that hypothetical person.

Katz sees HazAdapt as a tool that can assist people who frequent “college campuses, museums, theme parks, megachurches, those kinds of unique areas that people come to constantly,” the types of places where tragedy breaks out unexpectedly and rapidly.

An obvious flaw that comes to mind is that apps rely on a network connection; depending on the emergency in question, nearby Wi-Fi networks might go down. In the event of an internet outage, the app can use Bluetooth to link people. Additionally, the app can download infographics to a phone based on the user’s location and physical needs, so in the event you don’t have a connection during an emergency, you’ll have something to work off of.

Smart cities and the integrated future

HazAdapt’s attempt to channel interconnected tech for safety reflects a larger trend: The quest to build smart cities, cities where connections between devices — the “internet of things” — allow people to more efficiently manage resources and improve safety.

Katz is excited by the potential of smart cities, although curious about how they treat peoples’ data.

“What’s the security like? How are these systems balancing that need for integration with security? And that’s always a big concern for any developer, especially when you have so much heavy, granular data that you’re dealing with.”

Smart cities are all the rage these days, but how likely is it that HazAdapt fits into the interconnected ecosystem of the future?

The platform is still in development, with more testing over the coming months, with the aim of hitting the market in 2021. So far, emergency responders seem excited about HazAdapt’s platform.

“The main response that we keep hearing from emergency managers or the professionals that would use this is ‘Wow, we could have used this yesterday, and you guys are five years ahead of the market in thinking about this,’” Katz says.